And Happiness for All

On October 3, 2014, Jeong Eun Hwang (Communications Coordinator) and Dae-Han Song (Policy and Research Coordinator) of the International Strategy Center met with Kyung-Seok Park, the president of Solidarity Against Disability Discrimination and principal of Nodeul Disabled People’s Night School. (Interpretation by Jeong Eun Hwang. Interview by Dae-Han Song.)

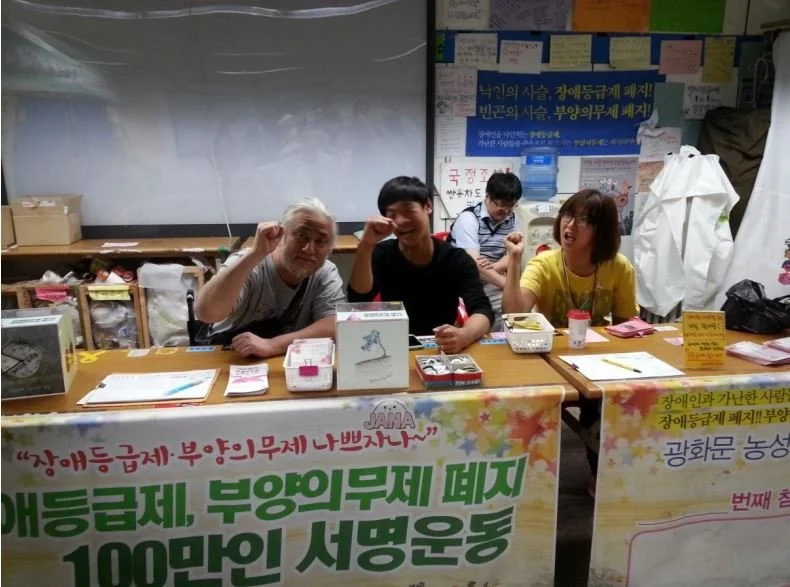

Kyeong Seok Park (on the left) with fellow activists in the Gwanghwamun Occupation Site

Can you give us a brief history of the disabled people’s movement?

Before 1980, the movement around disabled people revolved mostly around individuals signing petitions or providing welfare and services to disabled people. What could be termed the disabled people‘s movement began in 1980. That year, disabled students who had passed the university entrance exam applied for admission to university but were rejected because they were disabled. That‘s how the struggle against educational discrimination of disabled people started. Then in 1987-88, we organized around the 1988 Olympics and Paralympics. The disabled people‘s movement expanded greatly through that period of organizing. In 1999, we had another round of organizing and expansion with the struggle to reform the Physical and Mental Disability Welfare Law (which existed as an empty law) and to create a law promoting disabled people‘s employment. Then in 2001, disabled people‘s struggle is reframed as a human rights issue. That year, a disabled person died after falling off a wheel chair lift in Oido Station. This was a fight around mobility rights. During this struggle, we started to take to the streets. Our tactics became bolder and more radical like occupying buses and rail tracks. In addition, along with the struggle for mobility rights, we see the rise of the independent living movement.

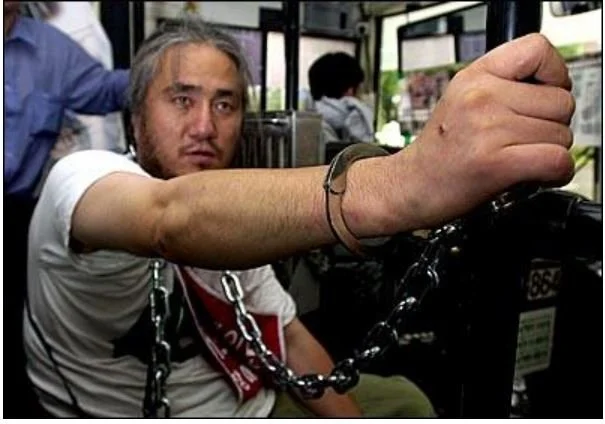

Kyung Seok Park chaining himself to a bus demanding mobility rights on August 29, 2001

Why do we see a shift from welfare projects to a struggle for human rights?

In 1980, the rejection of the disabled students was such a spark because you had students that had passed the test, that wanted to study, but were rejected simply because they were disabled. The wronged students organized press conferences and rallies. People could sympathize with the injustice. That was the beginning. In 2001 with the Oido Station accident, we realized that moderate actions couldn‘t create the big changes that were necessary. While it hadn‘t taken much money to just admit a few students, when we started talking about installing elevators in subway stations or providing low floor buses, that was a sizeable amount of money. People could sympathize with the idea, but they would balk when it actually came to implementing them. So we escalated our actions. We stopped buses and occupied rail tracks. These struggles brought public focus to the issue. As the number of people that became convinced that society should not continue in this direction increased, new laws were passed, buses were constructed, and elevators installed.

Did people’s consciousness shift along with this shift in the movement?

The way that others looked at us shifted from pity and charity to human rights and as protagonists of our struggles. For us, disabled people, we were able to recover our protagonism, self-respect, and confidence through this movement and struggle.

What were your most memorable struggles?

It was the struggle around the Oido Station accident. The Oido Station death happened in January 22nd. In protest, we occupied the subway tracks of Seoul Station on February 26th. We occupied it for almost an hour demanding that they install a station elevator. About 100 of us were arrested and many had to pay stiff fines.

Activists for mobility rights occupying subway tracks at Seoul Station for an hour (February 26, 2001)

Can you talk about the current struggle?

Our occupation of Gwanghwamun Subway Station, which started on August 21st, 2012, is currently on its 774th day in protest of the Disability Grading and the Family Support Obligation systems. The Disability Grading system was first established in the 1981 Physical and Mental Disability Welfare Law and actively implemented starting 1988. It ranks disabled people into six grades based on the severity of their disability. In 2007, an activity support service [which provides an assistant to a disabled person to help with his or her daily living] was established. This was the first direct support system for disabled people in Korea. Before, disabled people only received support indirectly in the form of free access to services or tax exemption.

However, the implementation of this service revealed the contradiction in the disability grading system. While those that needed the service numbered 350,000, the budget only allowed for 50,000. So, at first they limited this service to the 1st grade [the most severely] disabled people. After protestations, they expanded it to also include 2nd grade disabled people. Currently, only 1st and 2nd grade disabled people can get this service. We are proposing that instead of basing a person‘s eligibility to their disability grade, that each person should be evaluated separately for the service they are applying for. This is just a convenient way for the government to control and manage people.

The second issue is around income. If a person that is unable to earn an income has parents with a little bit of income or assets, then under the Family Support Obligation System, that person can‘t receive any assistance payments from the government. Even if that person were in his or her 30s, 40s, or 50s, that person wouldn‘t be able to get the income he/she needs to live. We are fighting for its abolishment. If a person has no income, then they don‘t have an income regardless of whether their family does or not. They should receive a minimum living income.

The reason why this is such a difficult struggle is because with the current welfare budget allocations, it‘s impossible to meet our demands.

Across the occupation site on a station wall: a shrine to martyrs

Your organization is called Solidarity Against Disability Discrimination. What would a society free of discrimination against disabled people look like?

That society should be one where not just the disabled, but all people can be happy. We need to ask ourselves: What kind of tools do we need to create this happiness? Right now we have a society of ruthless competition where only the successful survive. In this society, disabled people are treated as a special group to be helped. But the society that we are envisioning is one where everyone can be happy. While what makes each person happy may differ, it should at least provide the basic needs: food, shelter, health, a job.

So to create such as society we first need to disseminate the value of living together. Then that value should be supported by the law and the budget. After the universal adoption of such value, then if disabled people have extra special physical or mental needs, they should be addressed. The needs of disabled people should be addressed as part of a much larger effort for everyone‘s happiness. If we try to resolve the issue of disability rights without changing society‘s structure and values; if we view disability rights as an issue separate from society as a whole, then our issue can‘t but become distorted. This is the approach of capital, or those that rule.