Lula’s 3rd Term From the Perspective of Brazil’s Largest Social Movement: the MST

edited by: Matthew Phillips and Dae-Han Song

Ana Cha is a member of MST’s National Coordination and does work at the national school with the International and political education collectives. She has been a member of the MST for the past 20 years and became involved in the northeast part of Brazil. We interviewed her for our monthly ISC Progressive Forum on Sunday Feb. 19th. The interview was carried out by the International Strategy Center’s Zoe Yungmi Blank and Mike Cannon.

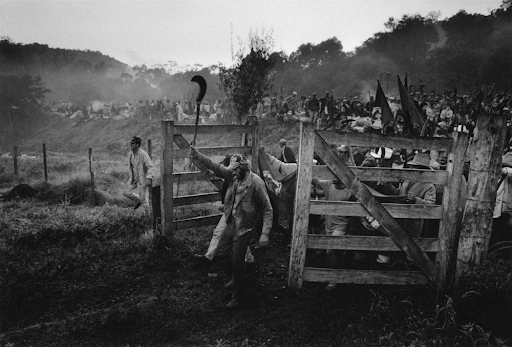

The MST has been called one of Latin America's largest and strongest movements, having emerged from dictatorship during a period of democratization in 1984. The MST now has a base of 1.5 million people and has settled 350,000 families with 90,000 families encamped awaiting recognition. The MST land occupations are justified under the 1988 constitution, mandating for land and to serve social function. Yes, for those of us living outside of Brazil or new to this issue, imagining tens of thousands of rural, landless workers entering private property and occupying it sounds radical, even revolutionary, and you've managed to settle 350,000 families in this way. What makes such radical actions possible?

In Brazil, 1% of the land owners own 50% of the land. When MST started to organize the workers in the early 1980s the vast majority of those lands were unproductive. And there was a huge contingent of people in the countryside who had no place to work or to live. There was even a very hungry [impoverished, immiserated] situation. So land occupation was and still is a tool to denounce this situation. Occupying the land has the main goal of putting pressure on the government to expropriate these lands for agrarian reform. Of course, these radical actions provoke a lot of violence on the part of the landowners.

In the Brazilian constitution there is a mandate as regards “the social function” of land which says that a land must be productive socially, that is it must be producing food and / or it must be producing a livelihood for families. If it is proven that that land is unproductive, the government must expropriate that land. Alongside land occupations, there are other forms of struggle such as negotiations, big marches, public acts to put pressure on the government. But our movement is a mass movement, constantly applying pressure all the time, being backed by the legal framework of the existing constitution, so we consider our actions here to be very radical, but from another point of view it is not so radical. Our successes are only possible because we are a mass movement who really organize a big amount of workers and landless.

So despite the legal justification, you mentioned that there still is strong resistance. How are the MST’s land occupations viewed by everyday Brazilians on the street?

These almost 40 years we have gone through different shades or sorts of support for the struggle of the Landless Movement by society. To simplify a little: I will say that the first years of MST our struggle was not well known for the majority of the population. But, if you lived near a place that had an occupation or a settlement, in general, you will support our struggle because it was a struggle to reduce inequality, to give land to those who wanted to work. At the end of the nineties the movement became better known partly because there was a big massacre of landless peasants and this situation was shown on TV and thereby generated a big solidarity movement. At that moment, even if the media tried to criminalize and discriminate against us, there was a lot of support from the population. The majority considered our struggle for the right to work on the land was just.

In the last 10 to 15 years, however, agribusiness has developed a lot with transnational financial capital. In our opinion, these transnational agribusinesses do not fulfill the social function of land because they only produce commodities to export. They have invested a lot in producing propaganda and publicity so as to create an ideological hegemony in Brazilian society. So this recent development makes it more difficult for us to put our disputes forward, with a changing popular notion about what is just and what is best for the countryside in Brazil. On the other hand, today, MST is widely recognized for its production of healthy food, for its proposal of agricology, for its proposal of education and rights for all, and for its role of solidarity with the poorest people in the city.

Remembering the opportunities and challenges from PT’s (Lula’s Workers Party) last period in power, what lessons will you and the MST remember as we move into Lula's third term now and has the MST ever considered creating its own political party?

Well, for us, regarding the first period of PT in power, something that was really new for us at that time was the open and direct dialog with the government. So PT gave visibility to the agendas of the social movements at that time and allowed the advance of several policies that directly favored workers and peasants in particular. Although at that time we had a lot of criticism, as regards agrarian reform, the PT government was the one that developed the project of agrarian reform by expropriating land, but also with important public policies for food, energy, credit, and housing. But at that time it was a government of a very big social coalition. So the support for the agribusiness and the large landowners was there, in exchange for political support. And that means the land concentration, for example, has not changed. And we still have many landless people. So for us the major lessons from that period are that we need to always maintain our independence, to build support in society, and always continue the struggle.

For MST, we struggle for land but also for social transformation for people's projects. A political instrument like a party cannot be only of one sector of society. It must be a party for the class. So at this moment we believe that we have parties to participate in elections and for us our biggest role is to do mass organization and to try to build a coalition of forces in society.

MST actively mobilized and organized for Lula, as well as running its own candidates. In the past October election it organized people's committees. Out of the 15 candidates the MST ran, 6 were elected. What does Lula’s victory mean for the MST and what opportunities open up from these MST candidates?

So, first of all, Lula's victory in the context that we were living in means that we have defeated Bolsonaro. And by defeating Bolsonaro, we open up a perspective of space to build democracy. So now we have again the opportunity to make political struggles and to have economic conquests. So this is very important because during Bolsonaro's government we have lost a lot of rights and people have seen their lives become even poorer. So with Lula, the people's agenda, it's again, on the public’s radar. And for us having six elected MSP affiliated candidates gives us the possibility of giving more visibility to the popular agrarian reform. So for us now it's a moment to do a lot of struggle but also to advance in the institutional struggle. So we believe that we are able to advance in the debates about public policies for the countryside and help to construct new legislation that support the struggles in defense, not just of agrarian reform, but also in defense of human rights and of food production.

The MST’s election organizing was very interesting. It wasn’t just getting votes, which is what we normally expect. Rather, you organize people into People's Committees. How many are there, how active are they and how are they engaging with the Lula government?

The idea was to organize for the elections, but also let people identify what the main needs for their communities were and the possibilities of doing struggles for a better life conditions. So because they're very rooted in the communities, they now have the possibility to also connect with the way we are building public policies. So we used to say that the People's Committee has this big task of re-enchanting people for politics again. It is not easy because we have a very demobilized society, but we firmly believe that this could be connected to building the future policies in many different areas. For instance, we have a Ministry of Culture again. All the resources and all the programs to strengthen the local culture actions will be through the People's Committees. So you need to be organized on a committee to be able to make the debate on how the money will be spent and how the programs will be developed. To strengthen people's participation we need to strengthen the People's Committees and combine these with the long and permanent process of popular education, of political training, and also a very intensive work of communication.

Lula's coming in and obviously he has a different tack from Bolsonaro, but, you know, he's going to be limited in what he can do. How, as a social movement leader, what is your perspective in regards to how you're going to engage with this new administration?

We live in a very difficult situation: almost all of the achievements under Lula’s first terms have been lost under Bolsonaro. The PT government doesn't have the majority in the national Congress. Also, Brazilian society is very divided. So we have very urgent challenges: we face hunger and unemployment but we also have a big challenge which is to win society to a People's Project of Brazil. As a social movement, we believe that we need to engage each day the biggest part of the society in the struggles in the demands for the government so that they can have political strength to accomplish necessary changes.

But on the other hand, we also believe that we have an expertise to offer in terms of food production, in terms of food sovereignty, in building policies that can directly address problems surrounding hunger and illiteracy. So we are participating with other social movements in articulating struggles for instance in putting forward a new minimum wage. So that's one of the struggles that we are engaged in now. But at the same time we are participating on the committees and on the councils to build food production policies and to build communitarian kitchens. And to build a program similar to Zero Hunger, directly addressing hunger and giving people better life conditions. So we are also within the government trying to advance quickly with these programs and public policies that connect agrarian reform and food production with solving the hunger problem.

Does MST have anything like an official position on BRICS economic development group?

Although we think we need to wait to see more how this global articulation will be consolidated in this new conjuncture, we see it has the possibility of really building a hegemony against US imperialism. For us, the possibility of a new currency is very important. So we are excited about the new role and new geopolitical position that BRICS can have in the next period. And we thoroughly believe that Brazil could now have a very important role on building BRICS in a more multipolar perspective. Governments need to build these global articulations and that they could be very important to go against U.S. imperialism. So all the initiatives like the BRICS, the ALBA, the CELAC, are very important. However, social movements also need to have international networks and international days of struggle. So that the agenda of these international and multinational organizations are not dominated by the economic and the neoliberal agendas, so they could have people in the center of the agenda. And so for that, we are also part of ALBA’s movement, which is a network in Latin America. We are part of the International People's Assembly, which is an international network of social movements and political parties. And we really believe that we need strength. That's why we're participating in forums like this, to strengthen the connections and the relations among the workers of the world.