Fighting the 24-Hour Workday

Greg Chung

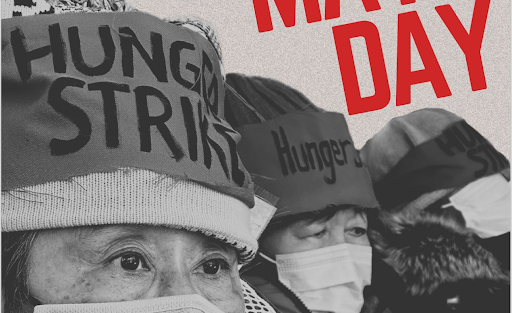

Youth Against Sweatshops May Day poster (twitter/youthasnyc)

Home care workers in New York City launched a hunger strike, demanding an end to the brutal 24-hour workday. An aging population and neocolonialism have turned homecare into one of the fastest growing industries in New York City. Global austerity and US-led military interventions force women of color to migrate from the Global South only to end up trapped in sweatshop labor. In South Korea, President Yoon Suk Yeol also wants to create his own sweatshops. This May Day, labor unions condemned the government’s proposal to address the declining birthrate by permitting employers to pay migrant care workers less than the minimum wage.

Unlike traditional labor campaigns, U.S. homecare workers have built a social movement that organizes homecare workers and the broader working class, as well as putting a target on US imperialism. Jun and Yolanda from Youth Against Sweatshops and the Ain’t I A Woman coalition spoke with the podcast Red Star Over Asia about home care workers' ten-year-long struggle against the 24-hour workday. This excerpt was edited for brevity and clarity, but you can listen to the full interview here.

What is it like to work in the homecare industry?

Jun: If you ride subways more than 50 percent of the ads are from home care agencies because of the aging population. If you're very old, sick, or disabled in some way where you need care for every hour of the day you will get care for every hour of the day. Only in New York City, those 24 hours are often one shift assigned to one worker and it's going to be at a patient's house or apartment. So these aren't hospitals, it's someone's cramped New York apartment, and what makes it particularly tough is these are extremely sick people who require 24-hour care.

Yolanda: What that means in terms of work is you help a lot of people who are bedbound. If they have to go use the bathroom, you walk them to the bathroom. If they're not able to, you're the one that changes the bedpans. You have to flip the person every hour so their bed sores don't get worse. To add to that, a lot of the patients have Alzheimer's so they would scream nonstop day or night, and then they would get up in the middle of the night to turn on the stove and it’s obviously the job of home care workers to turn the stove off. We have a lot of cases where in the middle of the night patients very quickly threaten to leave the house and then the home care workers have to go out and find the patients.

How often do homecare workers get 24-hour shifts?

Yolanda: Homecare workers usually work 24-hour shifts four to five days on average per week and they worked that for a decade on average. The homecare agencies like to lie. The bosses always say, “Oh you're lying you could get sleep at night so we shouldn't be paying your nightly hours.” So in addition to all the trauma to your health, 11 hours of nightly wages are being stolen every shift. The trauma is irreversible. When homecare workers visit China, they don't get jet lag because they just can't sleep at all. Even after they retire you just cannot sleep, your sleep system is completely destroyed.

A lot of the family relations are also destroyed. You go to work as your son goes to school but you never find out if your son actually did go to school or took the bus back and got into gang violence. This kind of trust with family members is not something that you can have economic compensation for. A Latina home attendant recently interviewed in the New York Times said that her son doesn't recognize her anymore, but she wishes that he would read the newspaper and know that his mother is fighting back.

Can you tell us homecare workers’ stories, where they immigrated from and why?

Yolanda: I speak Chinese so I work with lots of Chinese homecare workers, but we also work with Cantonese, Tai Shan, and Fujianese-speaking workers, as well as, Latina workers and newer immigrants from the Northern provinces in China. What unites all of them is that they realize that they come to the US for a better life because US imperialism keeps destabilizing economies abroad, but then they realize that their working and living conditions here are a lot worse than their home countries.

For example, when these workers left China, the economy was not doing well but people didn't work 24 hours nonstop. Many home care workers are driven by this betrayal, they think “I'm promised some opportunity for a better life in New York City, the heart of the US, but I end up in modern-day slavery.”

Can you explain how the Ain’t I a Woman campaign is different from a traditional labor union?

Jun: Yes, and I also want to say it’s not that a traditional union is incapable of doing the things that we do, but we are different in that we're not just fighting for small economic gains the way the AFL-CIO unions do, who fight for a five percent raise or maybe a little bit less hours. We're building a movement to improve our working conditions and bring the conversation away from economic to more radical and historically forgotten conversations, especially around the work day and length.

Two years ago, the largest union, SEIU 119 (member of the labor federation Strategic Organizing Center) sold homecare workers out with a “historic” 0.5 percent settlement when you would be working 24-hour shifts multiple days a week for 10 years, but you only get like $600 as a settlement and you basically give up all your rights to further pursue your claims legally, not to mention that the union doesn't mention a word to end 24-hour shifts going forward.

We’re trying to build a very broad coalition and what we mean by that is it's not just labor unions and activists. We're really trying to make a unifying call that this issue is not just confined to immigrant women in Chinatown. The New York Taxi Workers Alliance spoke and supported the hunger strike, as well as the PSC (the faculty union at the City University in New York). Also, during the whole six-day strike, bakers and restaurant workers made chicken soup

Demonstration by homecare workers (twitter/youthasnyc)

The Aint I a Woman campaign has emphasized organizing the community just as much as the workplace. Why did you choose such an unorthodox approach to organizing and how has it opened up opportunities that wouldn’t have been possible if you exclusively focused on the workplace?

Jun: Organizing within the workplace is getting more and more difficult. The gig economy fractures your workplace. The home care industry is split into a hundred-something agencies and workers don't really get to see each other. So how do we organize when we don't share the same workspace? We learned some amount of community organizing is very important. In the case of the home care workers, many of them live in Chinatown, that can be a very useful start, but sometimes we find that strategy almost holds us back and it becomes a Chinatown issue, so there’s a line that we have to walk between those two.

Yolanda: I think this also goes back to political education. We're constantly learning together.

Home care workers coming together in Chinatown realize that most of the home care workers are priced out of Chinatown now. So you know, in terms of community, they do find it very frustrating to have to take long commutes even though they do that all the time. They think that coming together and fighting for a better future for the next generation is worth the trip, it’s worth their time. But they also see that one of the largest home care agencies is developing luxury high rises in Chinatown and contributing to the displacement.

Also, the border between home care workers, restaurant workers, and even delivery workers is very murky. Many delivery workers have partners who work in the home care industry. More than just saying, “we're all workers so we support each other,” we need to maintain a network of Chinese-speaking immigrant workers of all industries and all generations grounded in all the fights that we face.

And the fact that folks are more dispersed and harder to organize today than in the 90s makes them fight and talk to each other more. They develop a deeper understanding that it’s not just a workplace issue, but also issues happening in our community. There's this old saying that if we allow someone to be slaves, then very soon we will become slaves ourselves right? So it's like we're next. After homecare workers, it's tech or educated workers joining the fight to end this extreme 24-hour work day

Slides provided by Youth Against Sweatshops (Instagram/youthagainstsweatshops)

Homecare workers have centered around anti-imperialism and international solidarity. Youth Against Sweatshops even tied the 24-hour workday to US military adventures and migration from the Global South. Can you explain why internationalism is so important and what that looks like in practice?

Yolanda: If we talk about who the community can be, I think that they see the US ruling class extract their sweat and blood money to fund weapons or wage wars abroad. After October 7th, we had 6 to 7 monthly rallies and protests in front of city hall and each time there were hundreds of home care workers plus supporters. I think that there was a special protest devoted to making the connections. Workers themselves and supporters are saying that we should end the war at its root right, that working people in the US have an obligation to stop building bombs for the US war machine. I think that fighting together definitely deepens our understanding of what kind of system we're up against.

Authors Final Remarks

We thank Jun and Yolanda for sharing home care workers struggle to end sweatshop labor in New York City. Homecare workers are arguing that the attack on their rights will spread to other industries, but it’s also true that it’s spread to other countries, as we are seeing with the South Korean government’s attack on migrant care workers rights. Home care workers have shown that we must move beyond trade union consciousness to a genuine mass movement that organizes workers where they live and where they work, grounded with an analysis of US imperialism and global capitalism.