Chinese Investment in Latin America

(Source: brics-info.org)

As the largest producer of goods in the world, [1] China hungers for raw materials and consumers for its products. Overinvestment and a slowdown in the global market is, also, driving China to seek out opportunities abroad. [2] On the other corner of the world, in “America’s backyard,” Latin American (LA) progressive governments are struggling to carve independence and self-determination by forming alliances with one another and diversifying their trading and investment partners. These two realities bring China and Latin America into an intimate relationship. For Latin America to not fall into China dependency while shaking off US hegemony, it will need a strategy to break from a global capitalist market and build an alternative socio-political regional system centered on the region and its people.

Ever since the 1980s (when it first opened its economy) until 2000, China was predominantly an importer of capital. [3] Foreign companies invested in Chinese factories to exploit its cheap labor force. Even as worker productivity increased, the government suppressed wages and devalued its currency to keep production competitive. Thus, China accumulated large foreign currency reserves. In 2000, to access raw materials and establish itself around the world, Chinese leaders initiated a “go global” strategy to encourage Chinese investment abroad.[ref]It went from 0.9 billion dollars in FDI outflow in 2000 to 116 billion dollars in FDI outflow in 2014. [4]

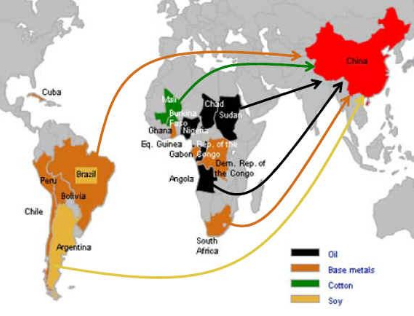

In Latin America, Chinese FDI stakes claims in raw materials, while alleviating excess capacity (exporting cheap electronics, workers, and construction capacity) in LA markets. While it is only 9% of total FDI in Latin America and the Caribbean, Chinese investment is dominated by the extraction of raw materials.[ref]Europe dominates at 40%, and the US is second at 18%. [5] While not necessarily benevolent, China’s state led investments (unlike global private companies) are driven by encompassing [6] that considers not just profits but also political, economic, and strategic interests such as long-term stable supply of raw materials [7] and diplomatic relationships. This allows greater flexibility for LA countries to pursue a wide range of objectives with Chinese state companies not possible with private US or European companies driven simply by short-term profits for shareholders.

While more flexible than other investments, Chinese investment, like other capital, nonetheless, contains an imperialist and potentially destructive character in its pursuit of profits, raw resources, and markets. This is particularly the case with one of its biggest exports: soybeans. [8] Argentina, Brazil, Uruguay, Paraguay, and Bolivia combined are the largest producer of soybeans in the world. Its greatest recipient is China. The soy beans are Monsanto GMO soy cultivated through heavy fumigation and little labor. 20 million hectares in Argentina are dedicated to soy production and 75% of this goes to China. [9] Soy production requires little labor – 1 worker per 500 hectares. Thus, as soybean plantations supplant fields that produced fruits, vegetables, and grazed cattle, farmers are displaced and forced to join the ranks of the poor in the cities.

Thus, Chinese investment provides opportunity and threat. For progressive governments to harness the opportunities while avoiding the threats, they must be guided by a larger strategy for socio-economic change and economic independence. Even as it sells hydrocarbons, minerals, and agricultural products to fund its social programs and development, these governments must wrest production from the hands of the domestic elite and wean themselves off from global markets to create a regional economy embedded on the needs of its people.

The seeds for such change have been planted. While Chinese FDI in Venezuela is predominantly in the oil industry, Venezuela’s Hugo Chavez managed to establish projects where China helped Venezuela develop via technology transfers through joint production of cell phones, appliances, and construction. [10] Revenue from oil was sowed into Venezuelan society and social and community programs and empowerment were harvested that have raised the expectations and consciousness of the population. Regional economic integration by the progressive governments through ALBA, while relatively small, attempts to create trade based on solidarity and cooperation. However, their growth and expansion is limited by the harsh conditions of a global market in which Latin America is in the periphery and a domestic market dominated by the national elite.

6 years ago, the Chinese state company Beidahuang had signed an agreement with the governor of an Argentine province to cultivate 300,000 hectares for food export to China in the Patagonia. It planned to bring Chinese workers to build the irrigation system. Yet, protests by local groups, unions, political organizations, and social movements sunk the project. In Brazil today, the Dilma government is faced with an impeachment process. Social movements are coming to defend her and democracy. Nourishing and bringing these seeds into fruition will ultimately be achieved not by the government but by the struggles of social movements.

Notes:

[8] The great demand for soy and corn is due to its ability to be processed into other goods. Corn can provide flour, oil, corn syrup; soy can provide protein and oil. These five elements are used as the primary resources for food products. When one eats processed food there is soy and corn. Secondly, China’s increased meat consumption means it needs lots of soy and corn to feed its chickens, cows, and pigs. Along with agrofuels, this has created the great demand for these goods. From interview with Carlos Vicente of GRAIN

[9] From interview with Carlos Vicente of GRAIN.

[10] “Venezuela’s Relationship with China: Implications for the Chavez Regime and the Region.”