What’s hot? Feminist media monitoring

By Dae-Han Song (chief editor, The [su:p])

A torso with a top revealing a full bust is printed on a mirror. The female target is supposed to reflect herself in the mirror and thus “try out” the full breasted torso. Whispers and thoughts surround the image: “Awesome,” “I envy you,” “These are mine?” A QR code takes you to the plastic surgery clinic that’ll service the transformation. In our next ad, “make me better” is written over a woman’s flat stomach, muscular butt and legs. In the next one, Korean ice-skater Kim Yun-ah’s body is sized up with measurements: the length of her legs, torso, and arms; the girth of her buttocks, quads, waist, and bust. If the ideal body is packaged for praise, envy, and consumption then the opposite is packaged for comedy. In two episodes of Korea’s favorite evening variety program “Infinity challenge,” one of the hosts pokes fun of the other two for being short and cute like children. Other hosts are teased for wearing clothes reminiscent of middle aged security guards.

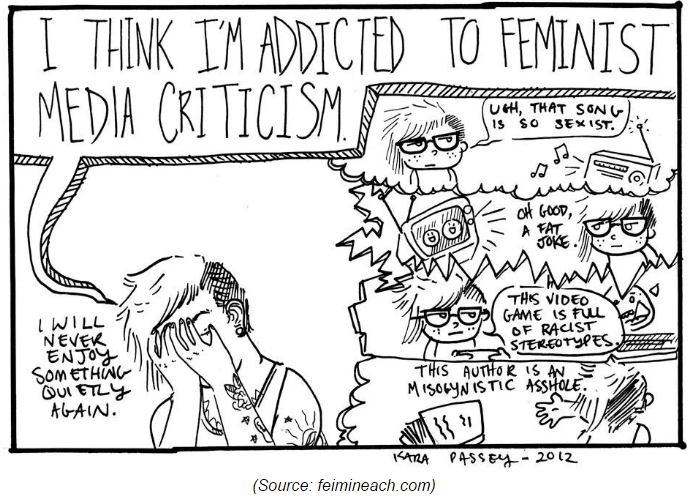

Both the ads and the episodes were chosen for the ISC Feminism study group’s media monitoring. If ignorance is bliss, then media monitoring is the opposite. To note the burden of knowing too much, a member posted in our chat room a cartoon of a woman with her face in her palms bemoaning ever enjoying anything again after practicing feminist media criticism. Indeed, two weeks reading feminist theory and media monitoring has questioned my idea of “beautiful” as natural and challenged my role in perpetuating the effort, pain, and control that goes into such construction.

“Beautiful” and “sexy” are not natural but are culturally determined. Susan Bordo's “Unbearable Weight” shows how in the 1950s full bodies such as Marilyn Monroe’s that represented maternity were beautiful. In modern times, as women joined the workforce and strove for careers in male dominated professions, trim bodies representing discipline and control were considered appealing. Based on what society desired and needed from women, the standard alternated between the two. Sometimes, it combined them as is South Korea’s current obsession with the S-line. A woman with an S-line must be both physically trim while having ample bosom and bottom. Thus, combined is society’s concern with the ethos of discipline women need to compete in male dominated professions but also the maternity needed to solve Korea’s low birth-rate crisis.

Bordo shows how these contradictions and tensions impact women, at extremes erupting into social symptoms such as anorexia nervosa where women try to excise the feminine from their bodies. To Bordo, anorexics are modern day ascetics, albeit tragic and misguided, striving for the male body that represents discipline and mastery. By eliminating fat and flab from their bodies, they rebel against the full bodied maternity of their home bound mothers. They do so at the cost of their bodies and for some, their lives. This effort at shaking free from society’s constraints is ultimately misguided as it fails to liberate their political consciousness. They seek equality not by battling society’s oppression but by eliminating the feminine within them.

This system that controls women’s bodies also impacts men’s lives. An ad for Absolut Vodka helped reveal this truth to me. In this ad, two attractive slender women in their 20s are sitting in a private room at a club bored and waiting for someone to complete the scene. Behind, a neon sign reads “The future is yours.” Men are the protagonists, and the two women are the supporting cast. The message is clear: the company of these two women, there to meet a man, is possible if the man can afford the room in the club stocked with Absolut Vodka. As products to be consumed, women must fit strict notions of beauty and social roles. Men as the consumer must be able to afford them. Thus, the image controls men through the market and women through their appearance and roles. Even though it contains neither camaraderie between the women, nor the potential of real love or joy with the viewer, we still consume the imagery much like we consume processed foods high in fat and sugar low in nutrition.

In modern society, processed foods are laden with fat and sugar in order to exploit our craving for high-energy foods wired into us from hunter-gatherer days. Our palates change as we grow used to these foods. It becomes more difficult to enjoy healthy food. In the same way, men’s consumption of these fabricated images of women change our perception of them and detract us from seeing them in their humanity.

In the Feminism study group, we study theory but are also challenged to apply it to our personal lives. It’s not simply about knowing but also about the responsibility that comes with knowing. When men objectify women by their appearance, we become accomplices in their oppression. If we are feminists seeking liberation, then we must stop perpetuating society’s obsession with women’s bodies. It’s not easy to change habits and customs. However, when we falter pulled back by our current world, we must change ourselves and society remembering that other world we are trying to create where people (he, she, they) treat each other with love and solidarity.