The Long Road to Peace in the Korean Peninsula: the South-North-Korea-US Summit

By Park Jae-seong (Steering Committee member, ISC)

2017 was a nerve-racking year for the Korean Peninsula, a tinderbox that could have exploded into war. In July, North Korea announced the successful launch of the long range Hwaseong-14 Inter-Continental Ballistic Missile (ICBM) putting U.S. states Alaska and Hawaii within shooting range. In September, in a speech to the UN General Assembly, President Donald Trump threatened to “totally destroy” North Korea if it threatened the United States. In November, North Korea responded with a 13,000 km long range Hwaseong-15 ICBM including Washington DC (11,300 km away) within its range.

In December, the U.S. carried out preparations for war in the Korean Peninsula. North Carolina’s Fort Bragg carried out exercises under live artillery with 48 Apache and Chinook helicopters simulating the movement of troops and equipment to assault targets at a scale not seen for years. Two days later, in Nevada, under cover of darkness, at twice the normal scale, 119 soldiers parachuted out of C-17 military cargo planes simulating a foreign invasion. Furthermore, mobilization centers were planned that could quickly move military forces overseas. On Jan. 16, 2018 the U.S. Pacific Command’s website announced, “Six B-52H Stratofortress bombers and 300 airmen from Barksdale Air Force Base Louisiana were deployed to Guam’s Andersen Air Force Base.” Three B-2 bombers were also deployed from Missouri’s Whiteman Air Force Base to Guam. The timing and scale of the exercises was particularly worrisome given rumblings within the Trump Administration of a “bloody nose” preemptive attack. The U.S. and North Korea needed a way out of this rapidly deteriorating stalemate.

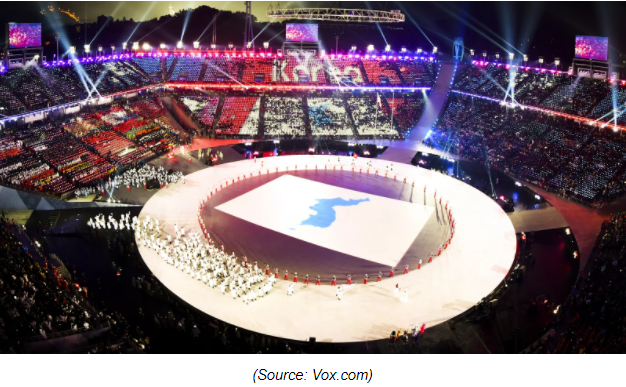

Peace Pyeongchang and a North-South Summit The Pyeongchang Olympics became the pivot for reversing the path away from war and towards peace. In June, during the opening ceremony of the 2017 World Taekwondo Tournament, President Moon Jae-in expressed his desire for a unified North-South team for the Pyeongchang Olympics. Three months later, in an interview, North Korea’s representative to the International Olympic Committee Jang Woong reversed an earlier stance by stating that “politics and the Olympics were a separate issue” and added that North Korea would participate in the Olympics if given the opportunity. On Jan. 1, in his New Year’s address, Chairperson Kim Jong-un moved further towards rapprochement stating the need to “make this into a historic year for improved inter-Korean relations.” Soon after, he announced his sister, Worker’s Party Central Committee Vice-Director, Kim Yo-jong’s participation in a high-level delegation to the Pyeongchang Olympics.

An understanding of North Korea’s assessment of the situation helps explain the sudden reversal. In his 38th North column, Alexander Vorontsov shares conversations with North Korean foreign ministry officials. Given Trump’s “America First” principle, the officials believed it very possible that the U.S. could accept the great loss of lives from a military conflict with North Korea. In contrast to their views, the South Korean public appeared to view the current crisis, tension and Trump’s belligerent rhetoric as mere posturing. The officials believed South Koreans did not fully grasp the possibility of a Trump preemptive attack on North Korea. While the military exercises might have been postponed due to the Pyeongchang Olympics, right after the Olympics, the exercises would become a hotspot with the potential to escalate tensions to dangerous levels. The only way to de-escalate and block U.S. preemptive attack would be a South-North summit to defuse tensions.

On Mar. 6, Moon reciprocated by sending his own special envoy to North Korea. The visit achieved an inter-Korean summit for April and explored the possibility of dialogue with the U.S. with denuclearization. Immediately after North Korea, the special envoy went to the U.S. to meet President Trump resulting in a U.S.-North Korea summit for May thus leading to the first important step towards peace. As mentioned above, several factors made this first step possible: North Korea’s pursuit of nuclear weapons as a means of balancing U.S. military might, the stalemate between a peace treaty and nuclear weapons between the U.S. and North korea, and finally, President Moon’s organizing of the Pyeongchang Olympics as a peace Olympics not just for both Koreas but for the world creating a space to actively pursue inter-Korean peace. Improved inter-Korean relations served as the foundation for resolving the situation and it was the candlelight revolution’s support of the Moon Administration that allowed it to actively pursue rapprochement so early in his term.

Nonetheless, the road to peace is long and unpredictable. Trump’s recent replacements for Secretary of State and National Security Advisor are more hawkish. In addition, the China-North Korea summit happened amidst growing tension between the U.S. and China for supremacy over Taiwan and the South China Seas. Both of these developments can threaten the current rapprochement between North Korea and the U.S. For those of us in South Korea, we must strengthen inter-Korean relations to stabilize the path towards peace. Beyond the April and May summits, several moments and anniversaries offer such opportunities: the June local elections with the potential to deliver a debilitating blow to conservatives (historically the greatest roadblock to rapprochement with North Korea), the anniversaries of the 6.15 Joint North-South Declaration, the 65th year of the ceasefire in Jul. 27, the 70th year since establishment of South Korea on Aug. 15, the 11th year since the October 4th Joint North-South Declaration.